CAP theorem is one of those ideas everyone knows, but very few actually design with. And that’s because it’s usually taught as a formula, not as a pressure situation.

So let’s do this the system designer way.

Assume you’re building a distributed system. Not a single server, not a single database. Multiple nodes, multiple machines, talking over a network. The moment you distribute a system, one thing becomes inevitable: things will fail. Machines crash. Networks slow down. Packets get lost. You don’t get to opt out of this.

Now CAP enters the picture.

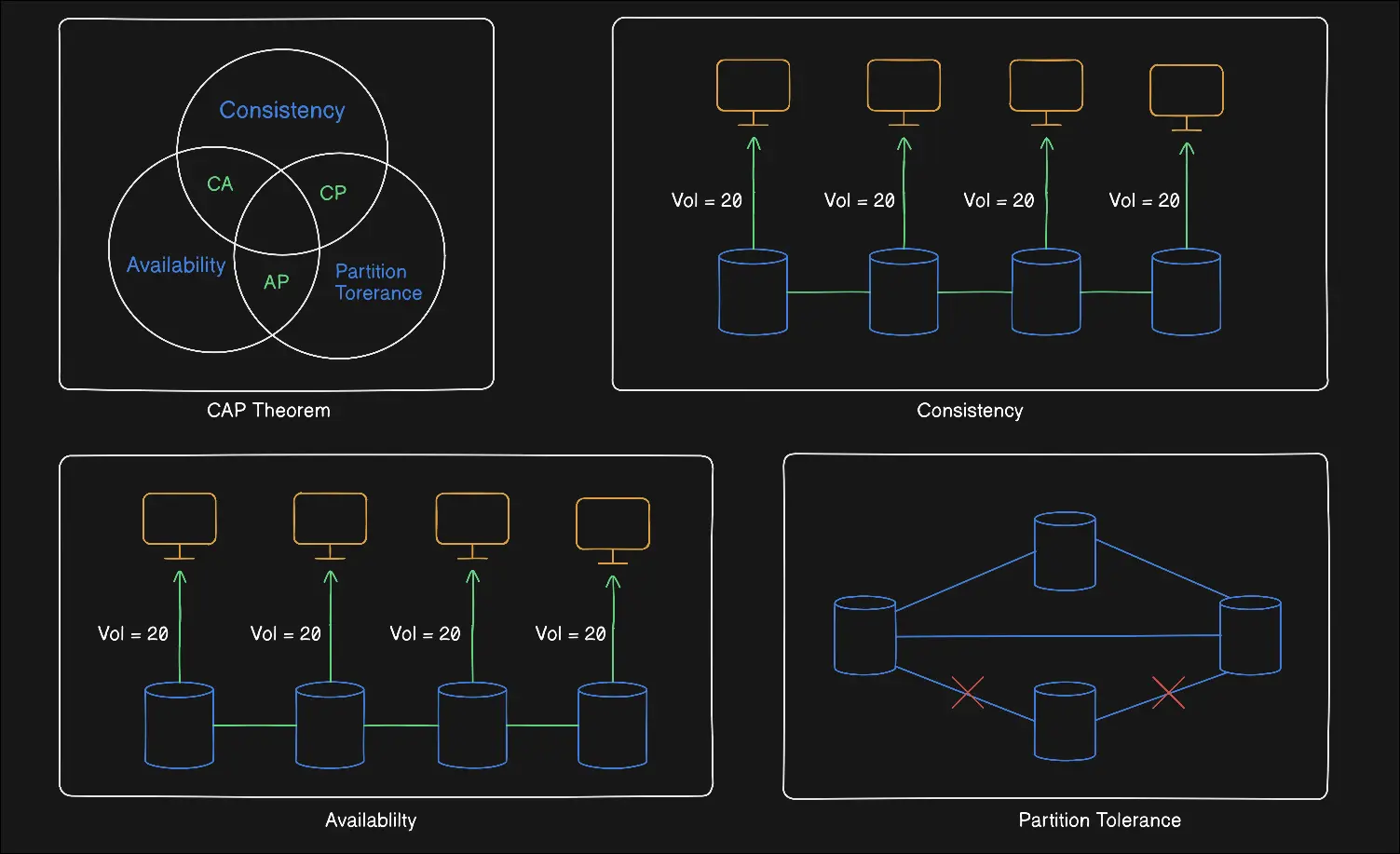

CAP talks about three guarantees your system might want: Consistency: every read sees the latest written data Availability: every request gets a response (not an error) Partition tolerance: the system continues to work even if network communication breaks between nodes

Here’s the key insight most beginners miss: Partition tolerance is not a choice in real distributed systems. Networks will fail. So the real tradeoff is never CA vs CP vs AP. In practice, it’s always Consistency vs Availability under a partition.

Let’s see what that actually means.

Imagine a distributed database with two nodes, Node A and Node B. They replicate data between them. Everything is fine until the network cable between them breaks. This is a partition. Now a user sends a write request to Node A, and another user sends a read request to Node B.

The system designer must answer one uncomfortable question: What do we do right now?

Option 1: Favor consistency. Node B refuses to answer reads because it might be outdated. The system returns an error or waits until the partition heals. Data stays correct, but users experience downtime. This is the CP choice.

Option 2: Favor availability. Node B answers the read using whatever data it has, even if it’s stale. The system stays responsive, but different users may see different data temporarily. This is the AP choice.

There is no third option. You can’t magically have both once the partition exists.

Now let’s ground this with intuition.

Think of a banking system. If your balance is wrong even for a second, that’s unacceptable. The system would rather say “try again later” than show incorrect data. Banking systems lean toward consistency, even if availability suffers during failures.

Now think of social media. If your like count is slightly off or a post appears a few seconds late, nobody panics. But if the app stops loading entirely, users leave instantly. These systems lean toward availability, accepting temporary inconsistency.

Same distributed reality. Different business priorities.

Another subtle point most people misunderstand: CAP is not about normal operation. During healthy operation, systems can often appear consistent and available. CAP becomes visible only during failures. And failures are exactly when architecture matters most.

This is why CAP is not a limitation. It’s a design lens.

It forces you to ask the right questions early: Is it worse to be wrong or to be down? Can the business tolerate stale data? What kind of inconsistency is acceptable, and for how long?

CAP theorem is not saying “you can only pick two forever”. It’s saying: when things break, you must choose what you’re willing to sacrifice.

Happy designing 🖤